Thanks to Outside Magazine for this:

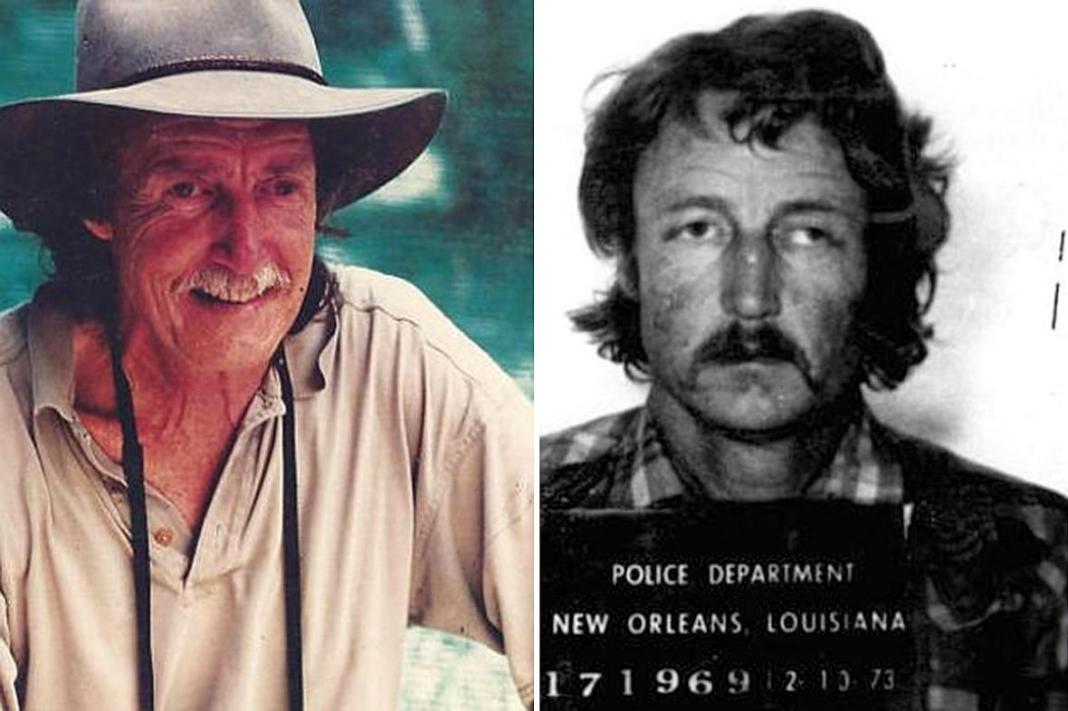

In June 1974, Florida’s Tampa Bay Times reported that Raymond Grady Stansel Jr was arrested for smuggling more than 12 tons of marijuana.

Then Raymond Stansel vanished.

He later turned up in Australia. And this is his unbelievable true story.

Even before he arrived at the accident scene, sergeant Matt Smith knew it would be bad. Smith was in charge of the 12-person police department in Mossman, a speck of a town located along Australia’s remote northeastern edge. He knew from experience that there was a fundamental truth about car wrecks: drivers have a pretty good chance of surviving a crash that’s car versus car, but they rarely walk away from a vehicle that’s slammed into a tree. The call that came over the police radio on that May 26, 2015 afternoon said that a vehicle had struck a tree along a two-lane road hugging the coastline. Smith’s hunch proved true. When he arrived, he found a white Toyota Hilux pickup wrapped around a gum tree as thick as a sumo wrestler. By some miracle bystanders had found a dog, an aging bichon frise, inside the truck, dazed but alive. But the driver had no chance.

Officers traced the registration to Dennis “Lee” Lafferty, age 75. Everybody knew Lee. Or at least knew of him. He was an American but had spent decades in nearby Daintree, where he operated one of the area’s oldest and most respected tour companies, running boat trips along the crocodile-filled Daintree River.

The river cuts through an ancient tropical rainforest that hosts one of the world’s most diverse ecosystems: rare ribbonwood trees, musky rat-kangaroos, and six-foot-tall southern cassowary birds. Lee was perhaps its greatest champion. It seemed there was no plant or animal he couldn’t identify, and his efforts to protect their habitats had earned him the reputation as one of the region’s most passionate conservationists.

Stansel would pilot his loaded-down boat into Florida’s maze of inlets. Under cover of darkness, they’d transfer the bales of marijuana, which “looked like horse feed,” right onto the beach, where they were weighed on massive scales.

“He was a real gentleman, a lovely man,” said Julia Leu, the mayor of the area. “He had a huge scientific knowledge, and he was definitely one of the people who wanted to preserve what we had.”

Smith spent most of his time at the crash site consoling a small crowd of Lee’s devastated employees, who told him that Lee shouldn’t have been driving. He was on medication for his Parkinson’s disease and prone to nodding off at any moment.

In the coming days, newspapers ran stories about the “local tourism stalwart” who “did not have a bad bone in his body.” There was a packed memorial service. And then everyone but Lee’s family began to move on.

Nearly four weeks after the accident, Smith received a text message from one of his detectives saying that he needed to read an article from a Florida newspaper about Lee. Smith was intrigued. Why would an American publication run a story about a guy in Daintree? The article had appeared in the Tampa Bay Times just a few weeks after Lee’s death.

Sergeant Smith isn’t the sort of person who is easily surprised or impressed. He once walked into a house that a spurned husband had booby-trapped with a speargun and barely flinched. Following a 2008 cyclone, he chased after a seven-foot-long crocodile gliding up a Mossman road. He has responded to multiple helicopter crashes in the area. When he learned what the article revealed, however, Smith was so amazed that he could utter only one word: “Wow.”

The piece described the life of an American fugitive named Raymond Grady Stansel Jr. In the 1970s, Stansel was a master fisherman who became one of Florida’s biggest pot smugglers, hauling gargantuan 12-ton loads hidden under piles of freshly caught fish. And then he pulled off one of the most dramatic vanishing acts of any outlaw in American history when he skipped bail, faked his own death, and reinvented himself in Australia as Lee Lafferty, tour operator and conservationist.

Since the summer of 2015, I’ve been trying to discover who Stansel truly was. What I ultimately learned—by digging through thousands of pages of court documents and interviewing his closest friends and family on two continents—is that the man lived not one extraordinary life but two.

The west coast of Florida is an angler’s paradise. People come from all over to fish for trout in Tampa Bay, grouper near Madeira Beach, and 100-pound tarpon in Boca Grande. Back in the 1960s, elite fishermen were treated like rock stars. They were invited to cocktail parties, and their exploits were chronicled in the newspapers. Raymond Grady Stansel Jr. was among them. “He was one of my heroes,” Bill Caldwell, who worked as Stansel’s deckhand as a teenager, told me. “He could do anything.”

Stansel was said to be able to back a 46-foot sportfishing boat into a slip with the wind blowing 15 knots and the tide running against him. Legend has it he once single-handedly brought up a 90-foot barge that had sunk in 100-foot waters using only scuba gear and inflatable tubes. He once caught more than 2,000 pounds of grouper in a single weekend. All this despite the fact that he was blind in his left eye, a consequence of being struck in the face with a broom as he and a friend swept the cafeteria floor in middle school.

Stansel was six-foot-two, lean and strong, with wavy dirty blond hair. He’d been raised in a modest house in Saint Petersburg, the son of a commercial fisherman and a Sunday school teacher. His renegade spirit and affinity for the outdoors emerged early in life. By age six, he could use a cast net to catch bait. As a teenager, incensed over the degradation of Florida’s wetlands, he boasted of sinking a massive dredge operating out of Tampa Bay.

When he graduated from high school in 1954, Stansel enlisted in the Air Force, gaining entry by memorizing the eye chart seconds before the exam. He told his friends that he went on to perform one of the Air Force’s most difficult jobs, refueling jets in midair, before he left the military and took up fishing as a profession.

There are several ways to make a living while fishing, from commercial jobs to running a charter boat. Stansel worked his way up to the best gig of all: private captain. He was hired by Clint Murchison Jr., the founder of the Dallas Cowboys, to pilot Murchison’s shimmering 40-foot Miss Centex in 1965. Stansel moved to the Texas side of the Gulf at Murchison’s request, bringing along his wife, Midge, and four kids—Raymond, Ronald, Sabrina, and Terry. They spent their summers in Boca Grande, where Stansel taught his kids to dive, fish for tarpon, and catch stone crabs.

By the late 1960s, though, the Murchison gig had ended. Stansel moved his family back to Florida and ran a charter boat, but the vicissitudes of the weather made things difficult. He tried to compensate for lean times by running stone crab traps in winter. But Stansel struggled alongside the other fishermen, most of whom kept their chins up and pressed on.

“Fishermen are like farmers,” said Bobby Buswell, a longtime friend. “You work your fanny off. You pay your taxes. You make a living. And that’s it.”

Stansel wanted more. There’s some disagreement as to how and when he was first drawn into smuggling. By one account, some dealers with a Jamaican connection approached him in the late 1960s because he was known as an expert boat captain and a family man unlikely to draw the attention of law enforcement. Another version had Stansel pulling off his first run in 1971, after he was recruited by two young smugglers who needed a bigger boat and were intrigued by the 44-foot T-Craft that Stansel had built himself. Wherever the truth lies, Stansel’s pot-smuggling enterprise was booming by the early 1970s. Marijuana was harder to come by in the U.S. in those days, a consequence of President Richard Nixon’s effort to shut off the flow from Mexico. But in Jamaica, buying a few ounces was as easy as buying a piece of fruit. “People would come off the street and offer to sell you their ganja,” recalled Mike Hubbard, who helped orchestrate one of Stansel’s earliest runs.

The marijuana was grown deep in the hills by villagers, who sold their product in 50-pound burlap sacks. Making connections was easy; transporting it back to the States—where it could sell for $175 a pound, a profit of $165—posed a challenge. So dealers turned to guys like Stansel, who knew practically every sheltered cove on the coast.

Word of this new source of income would eventually spread among Florida fishermen, but at the time, Stansel was one of the few players in the game. He soon expanded his operations into Colombia, which produced the most prized pot on the planet, by forming a partnership with a major supplier named Raul “Black Tuna” Davila-Jimeno.

Stansel would pilot his loaded-down boat five days from Jamaica (or ten from Colombia) into Florida’s maze of inlets. Under cover of darkness, they’d transfer the bales of marijuana, which “looked like horse feed,” according to one Stansel associate, right onto the beach, where they were weighed on massive scales. It took years for law enforcement to realize how much was arriving via the Florida coast. (In just two operations in 1974, they reportedly seized more than 200,000 pounds.)

To the guys on Stansel’s crew, smuggling came to feel like just another activity on the water. “We trusted each other. No contracts,” said Hans Geissler, a former French Foreign Legion soldier and elite sailor who Stansel recruited. “We were a pretty close-knit group. Sailing off the beach, jumping waves, surfing, Jimmy Buffett. It was a nice little crowd, and smuggling felt like part of it.”

Before the proceedings got under way, Stansel’s lawyer made a startling announcement: Raymond Grady Stansel had died on New Year’s Eve in a scuba-diving accident off the coast of Honduras.

Stansel soon had more money than he knew what to do with. For a while, he stacked $100 bills in orange crates in his parents’ attic. But when his father found them, Stansel looked for more sophisticated hiding places. He opened a bank account in the Cayman Islands, bought gold bars in Costa Rica, and set up seafood and boat-building companies in Panama and Honduras. He also bought something he’d need to expand his operation: more boats. Soon, workers at the pier noticed that Stansel routinely made trips to sea without any ice—a necessity for anyone planning to catch and sell seafood—and then returned with his vessel riding low in the water, nets bone dry.

On the morning of June 6, 1974, Stansel emerged from room 23 of the Sheraton Bel-Air, a luxury beachside resort in Saint Petersburg. Striding toward the parking lot with a brown briefcase in his hand, he blended in easily with the hotel’s well-heeled clientele. He folded his lanky frame into the driver’s seat of an Avis rental car, keyed the ignition, and turned north on Sunshine Skyway. Seconds later a group of unmarked police cars pulled out behind him.

Stansel had been under surveillance since he flew home from Central America a few days earlier. By now he was considered one of the state’s most prolific smugglers. Just after he turned off the highway, police radios crackled with news: a statewide grand jury had issued an indictment against him and three of his partners for conspiracy to possess marijuana. The officers flipped on their sirens and boxed Stansel in. They jumped out of their cars, ordered him to exit his vehicle, and cuffed him without incident. In his pockets he had $5,476 in cash.

At the station, officers cracked open his briefcase to reveal his other possessions: an additional $20,000 in cash stuffed inside a manila envelope; paper currency from Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Kenya; photographs of what appeared to be marijuana; blank tourist visas that would allow him to enter Nicaragua whenever he pleased; unused checks from a Swiss bank account; paperwork from Germany showing that his new Mercedes was ready to be picked up; and, finally, his passport, which was so thick that it stretched out like an accordion and indicated that he had been to 12 countries in the past 30 days, including Jamaica, Colombia, Japan, Hong Kong, Panama, and the Cayman Islands. The case against him was already strong—the cops had flipped several of his associates. With the items from his briefcase, Stansel would almost certainly do time.

He was booked on a $1 million bond. At a marathon three-day hearing, his lawyer, a federal prosecutor turned private attorney named Bernard Dempsey Jr., convinced a judge to lower it to $500,000. Three months later, Dempsey produced a cashier’s check in that amount, and Stansel was free. It was, at the time, the largest bond ever posted in Florida history.

The trial opened on a gloomy Monday in January 1975, and it promised to be a full-blown media spectacle. “For a Watergate-fed public still hungry for a big, juicy trial, today there is—Raymond Grady Stansel,” read an article that appeared that morning in the St. Petersburg Times. If convicted, Stansel could be sentenced to five years in prison (this was before the war on drugs), but he would likely face additional charges—and additional time behind bars.

Perhaps no one apart from Stansel had more riding on the trial’s outcome than Emiliano “E. J.” Salcines. The 36-year-old prosecutor had been handpicked by governor Reubin Askew to oversee the grand jury that indicted Stansel (and would later turn its attention to many other Florida drug-trafficking kingpins). Salcines was supremely confident. Even a lawyer as good as Dempsey would have little chance of freeing a guy caught with $25,000 in cash and photographs of marijuana.

Before the proceedings got under way, Stansel’s lawyer made a startling announcement: Raymond Grady Stansel had died on New Year’s Eve in a scuba-diving accident off the coast of Honduras. “He just went down and didn’t come up,” said Dempsey, who added that Stansel’s body had not yet been found.

Salcines seethed. He demanded proof of Stansel’s fate. “We insist not on any foreign documents,” Salcines shouted. “We want the body—dead or alive.”

The tips that came in over the subsequent weeks, months, and years were dizzying. Police departments across Florida were inundated with Stansel sightings reported by anonymous callers, confidential informants, and even jailed traffickers hoping to obtain early release. One week he’d be spotted at a brothel in Belize, the next drinking beer at a bar in St. Pete Beach, Florida. “It’s like chasing a phantom,” lieutenant Michael Hawkins, head of the Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office’s vice unit, told a reporter at the time.

“It was like Elvis,” recalled David McGee, who was a prosecutor assigned to a North Florida drug task force when the Stansel saga was playing out. “He became kind of a legend.”

The leads turned up only dead ends, but you couldn’t find a single cop in the state of Florida who actually believed Stansel was dead. “They’re saying he drowned in a scuba accident,” said one former agent with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. “That man had been on the water his whole life. He was like a fish.”

FDLE agents thought they had him in December 1976, when Honduran officials reported that Stansel had been “detained” in the capital of Tegucigalpa. The agency released a bulletin announcing his capture, and the news spread rapidly through Florida. Agents were preparing to catch a flight to Latin America when the Hondurans inexplicably reported that Stansel had vanished.

Wherever he was, investigators were fairly certain he wasn’t alone. Around the same time that Stansel had disappeared, so had his lover. (He and Midge were estranged by then, and Stansel’s kids were used to seeing him with other women.)

Janet Wood was a free-spirited twentysomething, blond and slender. Stansel first laid eyes on her while visiting the famed Chart Room bar in Key West in 1973. “He was the most exciting, extraordinary, capable man I had ever met,” she told me.

I first reached out to Janet a few months after Lee Lafferty was unmasked as Ray Stansel. When I finally heard from her ten months later, she made it politely clear that she wasn’t interested in speaking to reporters. “I have been offered money and the proverbial 15 minutes of fame (infamy?) and I was and am not interested,” she wrote in an e-mail from her home in Australia. She added that she was wary of how the couple might be portrayed. “We are never so uncomplicated as presented by the media with their limited space and time.”

After a correspondence that stretched to several weeks, Janet changed her mind. Stansel had protected her for so long, and now she felt an obligation to protect his legacy. If the story was going to be told, she realized that it wouldn’t serve the man she had loved to stay silent. “They may not be perfect human beings their whole lives, but there are individuals that make quite an impression on the planet,” she said.

Though she wouldn’t give up every detail, Janet finally told me how Raymond Stansel managed to make one of the most impressive escapes in American history.

Once he was released, local police followed Stansel wherever he went. They knew he had connections all over the world, and they didn’t want him to flee the country. In September 1974, barely a week out of jail, Stansel was on his motorcycle, riding away from the Tampa home where he was staying. As he crossed a bridge, he lost his tail, “dodging here, dodging there,” according to Janet. Then he made a dash to a local airstrip, where a friend waited with a private plane.

From there, Stansel flew to Key West to see Janet and convince her to come with him. “He didn’t know what he was going to do,” she told me. “He didn’t have a plan A, plan B, plan C.”

But he did have powerful friends. He somehow made it to Honduras—after all, he’d been smuggling drugs through the Gulf of Mexico for years. Once there, Stansel walked into the American embassy in Tegucigalpa and told officials he had lost his passport and needed a new one. (In fact, the police had kept it after his arrest.) Janet wouldn’t talk about his travel documents or the origin of his new identity, though records show that a 33-year-old named Dennis Lafferty had died in Florida just one year before Stansel slipped out of the U.S.

New passport in hand, Stansel went to the island of Roatán, 45 miles off the northern coast of Honduras, where Janet later met him. During Christmas week, his four kids—all between the ages of 11 and 16—joined them there. They dived during the day and spent the nights eating fresh fish and listening to Janet strum her guitar. A week or so later, the kids went back to their mom in the U.S., where authorities questioned Midge about Stansel’s whereabouts.

Ray and Janet, meanwhile, split ways en route to a predetermined location in Guatemala City. The plan was to sail across the globe in their 40-foot boat. The goal: end up as close as possible to the Great Barrier Reef.

They sailed to Belize, Nicaragua, Panama, Colombia, Aruba, Curaçao, and Bonaire. They went on motorcycle treks through Central American mountain ranges. They had a close call in Belize when Janet was mistaken for Patty Hearst and held for 24 hours.

It was an epic introduction to life on the run, and then Janet became ill. She suspected seasickness, but in Bonaire they learned that she was pregnant. Sailing around the world no longer seemed so appealing, so they decided to fly instead. First to Venezuela, then to Peru, Tahiti, and eventually the Pacific island of New Hebrides (now called Vanuatu), where they were married less than two weeks before Janet suffered a miscarriage.

Through it all, the couple were looking over their shoulders for whoever was surely hunting them, even as they boarded a plane for what they hoped would be their final destination: Australia.

The couple were looking over their shoulders for whoever was surely hunting them, even as they boarded a plane for what they hoped would be their final destination: Australia.

“For the authorities searching here and there, on the island and God knows where else, it was a job,” Janet wrote in an e-mail. “I do not say this to dismiss a few hard-working professionals, but their devotion to duty can’t compare to devotion to a dream of life, love, and freedom.”

There’s a saying in Australia’s Far North Queensland region: Your history starts here. For decades this remote stretch of pristine beaches and lush rainforest along the continent’s northeastern edge has attracted an oddball mix of Australian hippies and starry-eyed foreigners seeking a fresh start. You could be a German count or a renegade chemist who supplied LSD to the Grateful Dead. “No one gives a stuff,” said Andrew Forsyth, himself a former pilot who ferried Pope John Paul II and Queen Elizabeth around the world, and relocated to the area in 2002 after first visiting some 40 years prior.

In the 1970s, there were no traffic lights and few paved roads. Despite its proximity to the Great Barrier Reef, only the most determined travelers ever reached the area. Those who did often stopped in Port Douglas, a sleepy fishing village with a crescent-moon-shaped slice of golden beach. The downtown had a general store, a post office, and a couple of pubs where barefooted locals with names like Pegleg Tommy spun tales of bull sharks seen and giant crocs narrowly avoided.

“You could fire a gun down the street and you wouldn’t hit anybody,” said Norm Clinch, a machinist from Brisbane who often fished out of Port Douglas. “The police? There was one station, and they’d all be in there drunk or asleep.”

It was here in Port Douglas that, one day in the fall of 1975, a beat-up faded green station wagon arrived carrying a sun-baked American couple looking for just such a place. The lanky man who stepped out of the car identified himself as Dennis “Lee” Lafferty. If anyone asked—and few ever did—he was a fisherman from Texas. His wife was Janet Lafferty. If anyone asked—and few ever did—she came from Michigan, and both her parents were dead.

It wasn’t just Australia’s far-off location and proximity to the reef that attracted the couple. Lafferty’s great-uncle had visited in the 1920s and described Far North Queensland as a real-life Shangri-La. It also offered an added benefit: the fishing was world-class.

“We started from the get-go,” recalled Janet, who acted as Lee’s second mate as he relaunched his career.

The waters off Port Douglas were so well stocked, fishermen needed nothing more than a rudimentary lure made out of a four-inch piece of curved metal with a hook attached to have success. It was almost comically primitive. “When was the last time a fish saw a school of spoons going by?” Lee would say.

Lee outfished the locals in part by using live bait—caught with the specially designed cast nets that he and Janet made and sold—and quickly established himself as one of the best Port Douglas had ever known. “I used to say, ‘I’ll back Lee against any of you cunts,’ ” said Clinch, the salty-tongued machinist, who became one of Lee’s first friends. “ ‘He’ll fish you out ten to one.’ ”

If Lee did have access to large sums of money (and Janet insists that he did not), he surely didn’t act like it. At one point, he was running so low on cash that he had to borrow $8,000 from a fellow American expat named Walter Starck to buy an engine for a new boat. “He never bought anything flashy,” Starck said. “They didn’t go out and entertain. They lived a very modest life.”

Five years passed, and no one came looking for them. By then the Laffertys had two daughters—Jessie, born in 1976, and Kianna, in 1980—and though they told the girls about their past, life seemed to settle down. “He was a gentleman’s gentleman,” said Edward Pitt, a local fisherman who lived a few doors down. “He never showed off. He struck me as just a normal worker.” When pressed, his fishing buddies said there was one thing about Lee that was a bit odd. Anytime one of them produced a camera, he would disappear.

In 1982, the Laffertys purchased an overgrown piece of property along the Daintree River’s southern bank. The 80-mile-long waterway snakes through dense rainforest, where you can walk for miles without encountering another human being. It’s the kind of place that would have obvious appeal to an international fugitive.

But rather than retreat from society, Lee started a tour venture. The area has always been an ecological wonder, boasting unique species of mangrove trees, bats, birds, frogs, and tree kangaroos. He founded a company focused on exposing people to the best of it. In a span of ten years, the Daintree River Cruise Centre became one of the area’s most vital businesses. “It was classic hiding in plain sight,” Janet told me. “It’s not hard to turn the conversation around and get someone talking about themselves. We both learned that very quickly.”

Lee devoured books on the region’s ecology. He talked to the indigenous population to learn how they used seeds and plants. It wasn’t long before people showed up carrying specimens they hoped Lee could identify.

“I’d say, ‘God, he’s an encyclopedia,’ ” recalled Betty Clinch, who was one of the Cruise Centre’s first employees. As Lee’s understanding of the region’s ecosystem deepened, he dedicated himself to protecting it. He urged farmers to plant vegetation along the river’s edge to stop erosion. He pushed boaters to reduce their speed on the water so that the wake wouldn’t undercut the banks and disturb the microbes that inhabit the shallow areas. People close to him estimate that he saved the lives of hundreds of fruit bats that got stuck in the barbed-wire fences used by farmers. How he could spot them with one eye while driving on curvy country roads no one could understand. “Everybody here hates fruit bats, because they eat crops and spread disease,” said Lydia Archer, a longtime family friend. “He’d say they’re the most essential part of the ecosystem, because they spread native seeds throughout the forest.”

Even Norman Duke, one of the world’s foremost authorities on mangrove forests, was impressed. He first met Lee in 2002, when Lee was hosting a research expedition. “He really knew his stuff, and that shined in a place where there are a lot of people who don’t know what they’re talking about and claim they do,” Duke told me. “He easily fit into the tradition of the classic outdoor woodsman, the guy who can make a fire out of nothing in a rainstorm.”

For more than 35 years, Lee and Janet lived peacefully on the river. Then, in June 2011, news broke in Far North Queensland that a fugitive American drug trafficker was living an hour from Daintree. Michael McGoldrick, real name Peyton Eidson, was the leader of a California smuggling ring and went on the run in the mid-1980s. Eidson and his wife and daughter had fled to Australia, where they operated a luxury mountain retreat. They were captured by Aussie police after American authorities discovered that the real McGoldricks were dead.

For weeks the story was the talk of the Cruise Centre. The workers would sit around after-hours talking about the latest developments. It seemed everyone had something to say—except Lee.

Privately, Lee and Janet were both rattled by Eidson’s unmasking. “It did cause some concern, and it did worry Dad,” his daughter Jessie told me. “He certainly did not want to be exposed.”

Lee and Janet had ferociously guarded his secret since arriving in Australia. They had few close friends; he rarely left town and never returned to the U.S. Even after the two separated, in 2011, Janet never said a word to anyone. As careful as they were, the secret still found its way outside the family. When Kianna and Jessie were teens, they took equestrian lessons from a future Olympian named Christine Doan. Years later, Jessie married Doan’s brother and told him about her father’s past. The relationship soured, and so did the Doan family’s feelings about the Laffertys. “It’s a psychological crime scene,” Christine told me.

Lee may have succeeded in hiding his worries about Eidson’s arrest from his employees. But the noose was beginning to tighten.

Three years after Eidson’s capture, in late 2014, a tipster contacted a semiretired Florida newspaper reporter named Lucy Morgan and alleged that Ray Stansel had been living a second life as an environmentalist in Australia. Morgan was used to getting tips about Stansel; she was a 74-year-old Pulitzer Prize winner who had written numerous stories about him and other smugglers. The tip didn’t seem especially promising at first, but she wasn’t the type to let something go without a little investigation. Following the call, Morgan pulled out a set of dusty cardboard boxes that contained every available record on Raymond Grady Stansel Jr.

Lee Lafferty was by then a shell of his former self. Parkinson’s disease had sapped his strength and stiffened his body. His hands shook, making it difficult for him to hold a coffee cup. Walking became a chore.

Every so often he’d say something about his past that raised eyebrows—that he once slept with $2 million under his pillow, for instance—but his employees shrugged the comments off as the medication-induced musings of a sick man.

In early May 2015, a friend took him out in a wooden dory. For weeks, Lee had been begging his buddy to do so. Since he was a boy, there was nowhere Lee felt more capable, more alive, than on the water. But on the river that day, Lee could hardly move on his own; the friend had to lift him into the boat. After less than an hour, Lee said he’d had enough. A couple of weeks later, Lee Lafferty got into his pickup truck for the last time.

Back in Florida, the news of Ray Stansel’s death—and life—in Australia stunned the investigators and prosecutors who had spent years trying to bring him to justice. “He turned out to be a hell of a Houdini,” Salcines, the prosecutor, told me.

His family in Florida had more complicated feelings. “It really just broke my heart when he disappeared,” said his sister, Elaine Schweinsberg. “He never tried to contact us again. I felt so bad that his children had to grow up without him.”

In the years after Stansel vanished, two of his sons, Raymond and Ronald, became drug smugglers and then fugitives after they were indicted for trying to haul half a ton of cocaine into Florida in 1991. Both were eventually arrested—Ronald in Costa Rica in 1992, Raymond in Alaska in 2010—and handed long prison sentences.

Despite being abandoned by their father, both believe he made the right choice. “I think my father picked a good place to have a life and am glad that he won and got out of here when he did,” Raymond Stansel III wrote from the Coleman Federal Correctional Complex near Orlando. “I missed him but used what he taught me and lived without regrets for my life.”

“I don’t blame Dad for not showing up,” Ronald Stansel wrote from the Federal Prison Camp in Pensacola. “I’m sure that he missed certain aspects of what was left behind. It’s like you cut a chunk of your heart out leaving. But things seldom end the way you visualize in life. You can only take your best shot and roll with the punches.”

In fact, it was hard to find a single friend or family member who was troubled by Lee Lafferty’s previous life as a pot smuggler; it even seemed to have made him a legend. “Some people were asking does it change my opinion of him,” Mick Casey, a river guide who worked for him, told me. “It makes me admire the bastard even more.”

People in Far North Queensland often talk about Lee as someone who found redemption: a man running away from a troubled past who transformed himself into a protector of one of the world’s most pristine natural habitats. “Reflecting on it now, it’s just what Australia’s all about,” said Norman Duke. “It’s all about redemption. All about finding a new life.”

Spend long enough in Daintree, and you might also hear another story. Sometime in the early 1980s, Lee and a doctor friend were driving along the road that links Daintree and Mossman. As they neared a small bridge, they spotted a car in the crocodile-infested creek below. A couple of guys were just standing around looking at it. Lee burst from his vehicle and quickly realized that someone was still in the floating car. He dove into the creek, pulled out the unconscious man, and dragged him onto the bank. By the time the police arrived, Lee was long gone.